- Topic

47k Popularity

30k Popularity

52k Popularity

18k Popularity

51k Popularity

20k Popularity

8k Popularity

5k Popularity

97k Popularity

29k Popularity

- Pin

- 🎊 ETH Deposit & Trading Carnival Kicks Off!

Join the Trading Volume & Net Deposit Leaderboards to win from a 20 ETH prize pool

🚀 Climb the ranks and claim your ETH reward: https://www.gate.com/campaigns/site/200

💥 Tiered Prize Pool – Higher total volume unlocks bigger rewards

Learn more: https://www.gate.com/announcements/article/46166

- 📢 ETH Heading for $4800? Have Your Say! Show Off on Gate Square & Win 0.1 ETH!

The next bull market prophet could be you! Want your insights to hit the Square trending list and earn ETH rewards? Now’s your chance!

💰 0.1 ETH to be shared between 5 top Square posts + 5 top X (Twitter) posts by views!

🎮 How to Join – Zero Barriers, ETH Up for Grabs!

1.Join the Hot Topic Debate!

Post in Gate Square or under ETH chart with #ETH Hits 4800# and #ETH# . Share your thoughts on:

Can ETH break $4800?

Why are you bullish on ETH?

What's your ETH holding strategy?

Will ETH lead the next bull run?

Or any o

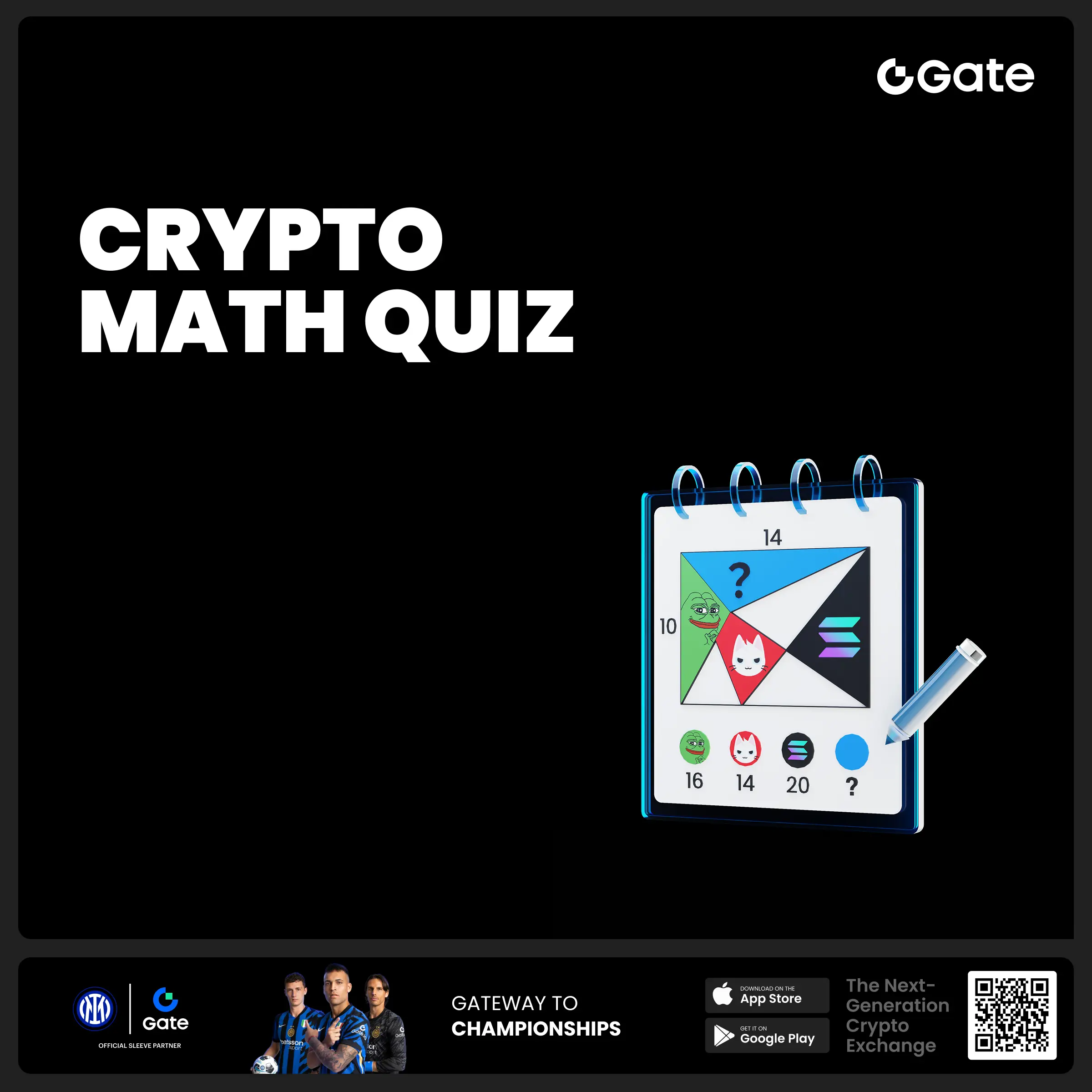

- 🧠 #GateGiveaway# - Crypto Math Challenge!

💰 $10 Futures Voucher * 4 winners

To join:

1️⃣ Follow Gate_Square

2️⃣ Like this post

3️⃣ Drop your answer in the comments

📅 Ends at 4:00 AM July 22 (UTC)

- 🎉 [Gate 30 Million Milestone] Share Your Gate Moment & Win Exclusive Gifts!

Gate has surpassed 30M users worldwide — not just a number, but a journey we've built together.

Remember the thrill of opening your first account, or the Gate merch that’s been part of your daily life?

📸 Join the #MyGateMoment# campaign!

Share your story on Gate Square, and embrace the next 30 million together!

✅ How to Participate:

1️⃣ Post a photo or video with Gate elements

2️⃣ Add #MyGateMoment# and share your story, wishes, or thoughts

3️⃣ Share your post on Twitter (X) — top 10 views will get extra rewards!

👉

A Review of the 2015 Bitcoin Garbage Transaction Attack: Prelude to the Block Size Debate

Recently, there has been a suggestion to remove the policy limits on OP_Return output size in the Bitcoin Core software library, sparking a new round of discussions about spam transactions on the Bitcoin blockchain and their handling methods. This article reviews the spam transaction attack that the Bitcoin network suffered in the summer of 2015, comparing the situation then with now, and discusses the lessons learned at that time.

The summer 2015 garbage transaction attack was an early skirmish in the block size debate. The attackers were from the faction that supported increasing the block size limit, believing that the 1MB limit was too small and easily filled with garbage transactions. Those in favor of larger blocks argued that filling up blocks would make Bitcoin payments unreliable, and that the block size limit should be increased to raise the costs for garbage transaction senders.

Supporters of small blocks believe that allowing junk transactions to be quickly and cheaply processed on-chain does not prevent attackers, but rather enables them to succeed. Increasing the block size would also lead to lower fees, making junk transactions cheaper. However, large block supporters focus on the total fees for filling a block, arguing that this value is too low for the security of Bitcoin.

On June 20, 2015, a Bitcoin wallet and exchange named CoinWallet.eu announced that it would conduct a "Bitcoin stress test." They claimed to prove the necessity of increasing the block size limit, planning to generate 1MB of transaction data every 5 minutes, with the goal of creating a backlog of 241 blocks. However, the first round of the attack did not succeed as expected, as the attackers' server crashed after the mempool reached about 12MB.

On June 24, CoinWallet.eu announced that a second round of attacks would take place on June 29. This attack seems to be more effective, with some users complaining that Bitcoin has become unusable. However, some mining pools like Eligius successfully filtered out spam transactions, resulting in their block size being significantly smaller than other mining pools. This has sparked a debate about whether miners should filter transactions, with some arguing that it undermines the fungibility of Bitcoin.

On July 7th, the third round of attacks occurred, larger in scale and with more diverse strategies. The attackers spent over $8000 in fees, sending a large number of small transactions to public wallets and known private key addresses. Some developers believe that increasing the Block size is the best defense measure, while some mining pools clean up junk outputs by creating large consolidated transactions.

In September, the final round of attacks was carried out, and CoinWallet.eu publicly released thousands of private keys containing balances, resulting in over 90,000 transactions. The impact of this attack was not as severe as before, and many conflicting transactions could be discarded using the "first-seen security" principle.

These attacks had a significant impact on Bitcoin. Miners raised the block size limit policy to 1MB, the minimum relay fee increased by 5 times, and Bitcoin Core introduced memory pool limits. At the same time, these events exacerbated the divisions in the block size limit debate.

Compared to 2015, the scale of "garbage" transaction fees has now reached hundreds of millions of dollars. However, the debate over how to define and handle garbage transactions continues. This history shows that garbage transaction attacks are nothing new, but their scale and nature have changed significantly.